Consequences of Undecidability in Physics on the Theory of Everything (PDF) from Journal of Holography Applications in Physics - June 2025.

General relativity treats spacetime as dynamical and exhibits its breakdown at singularities. This failure is interpreted as evidence that quantum gravity is not a theory formulated within spacetime; instead, it must explain the very emergence of spacetime from deeper quantum degrees of freedom, thereby resolving singularities.

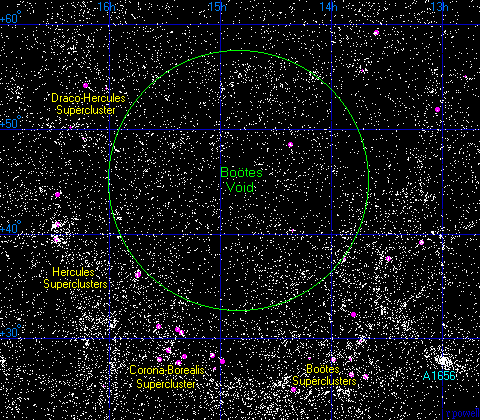

Quantum gravity is therefore envisaged as an axiomatic structure, and algorithmic calculations acting on these axioms are expected to generate spacetime. However, Gödel’s incompleteness theorems, Tarski’s undefinability theorem, and Chaitin’s information-theoretic incompleteness establish intrinsic limits on any such algorithmic program. Together, these results imply that a wholly algorithmic “Theory of Everything” is impossible: certain facets of reality will remain computationally undecidable and can be accessed only through non-algorithmic understanding.

We formalize this by constructing a “Meta-Theory of Everything” grounded in non-algorithmic understanding, showing how it can account for undecidable phenomena and demonstrating that the breakdown of computational descriptions of nature does not entail a breakdown of science. Because any putative simulation of the universe would itself be algorithmic, this framework also implies that the universe cannot be a simulation.

Setting aside the question of whether any of this is provably true (or relevant to the subject of this thread) it seems there’s an existential anxiety in philosophy and science confronting the raw living reality that refuses to be reduced to logic and algorithms. The subject and user is not code, at least not entirely. The world can never be fully modelled, computed, and made legible by the state seeking total control.

(Note to self: Start dystopian sci-fi music/video album, Tentacles of the Mammon Matrix. First song “Escapology”.)

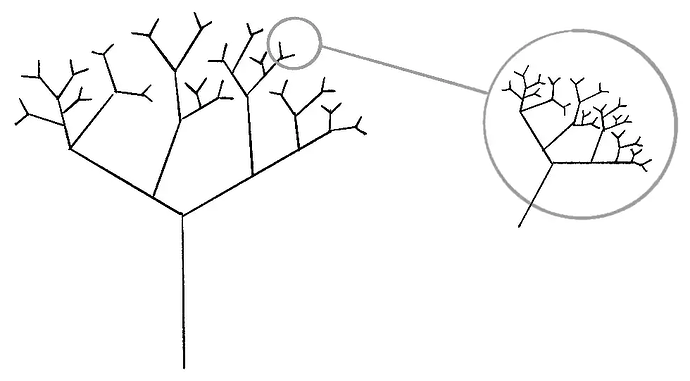

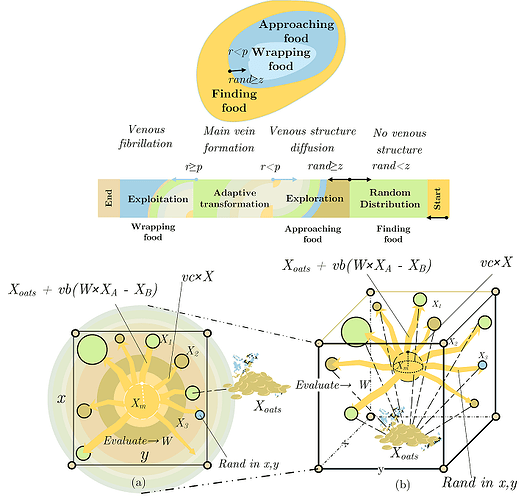

This undecidability in physics may be related to chaos theory and fractals in natural systems. Feedback loops, self-organization, replication and recursion approaching infinity.

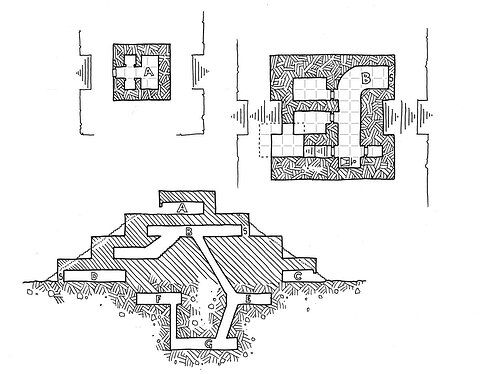

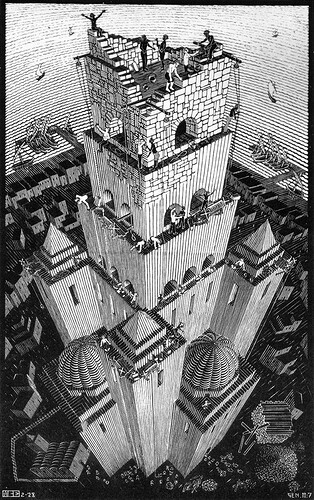

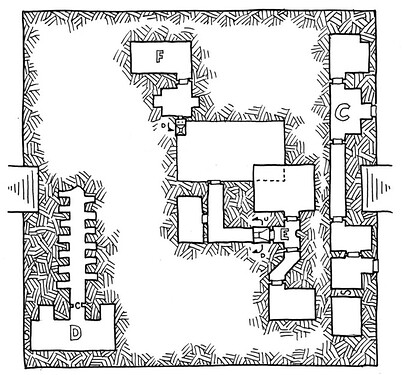

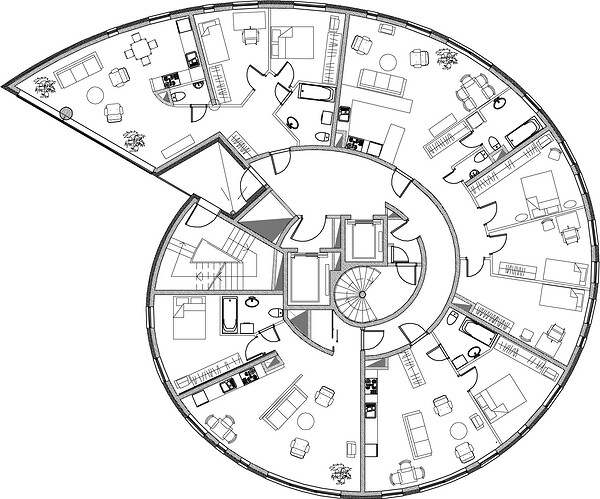

(From Nature of Code by Daniel Shiffman - Chapter 7: Fractals)

An interface or language serves to reduce the complexity of the system and the user’s thoughts and intentions into a limited vocabulary with enough expressivity to perform communication and computation. (But not too verbose, beware the Turing tarpit.) Hm right, that’s what it’s for - the purpose of abstraction, “the process of generalizing rules and concepts”. We can only think by abstracting the world and any system we interact with.

Anatol Rapoport wrote “Abstracting is a mechanism by which an infinite variety of experiences can be mapped on short noises (words).”

An abstraction can be constructed by filtering the information content of a concept or an observable phenomenon, selecting only those aspects which are relevant for a particular purpose.

What’s perplexing is that a single button or a couple of instructions is sufficient interface for a Turing-complete system. The minimalism of lambda calculus and combinatory logic, like in Programming with Less than Nothing, feels like watching a magician conjure an entire computation stack from a handful of symbols and rules.

It’s satisfying to get to the bottom of things, to break down a system into the smallest units and understand it thoroughly, to achieve total transparency and malleability. For me that’s the charm of Uxn or LÖVE, an endlessly expressive medium made of simple words. Also self-hosted languages like Guile and bootstrappable builds project like Mes, GNU+Linux from scratch with mutually self-hosting Scheme-to-C and C-to-Scheme compilers.

Inspired by autopoietic projects like these, I’ve continued exploring Lisp, WebAssembly, C.

Recent experiments include:

wasmos- a microkernel that runs Wasm binaries natively- Also trying a variety of smol Linuxes like Alpine, Tiny Core, ToyBox

uscheme- a tiny Scheme (5 keywords) to C compiler written in itselfcc-wasm- C99 to WebAssembly compiler that can compile itself- Runs anywhere Wasm can, including browser.

ulisp-c- C99 port of uLisp (originally written for embedded systems)

Using Zig to cross-compile single-file executables- CPU architectures: x86_64, aarch64, riscv64, i386, wasm32

- Operating systems: linux, macos, windows, freebsd, UEFI

- CodeMirror editor with Lisp and C99 language features and structural editing

- Parser, linter warnings and errors, formatter, inline help, autocomplete suggestions

- Live editing of running programs

For now I’m trying to integrate a Lisp to C compiler written in Lisp; and a C to Wasm compiler written in C. The latter is small enough, I’m hoping, for the Lisp to gradually consume it like a slime mould and become a single self-hosting Lisp to Wasm compiler.

In parallel I’d like to direct the Lisp organism to digest HTML/CSS/SVG/MusicXML et al, into a new whole: a cross-platform DOM (document object model); design system (styling primitives); and declarative behaviors with signals and/or state machines. All integrated as a single programmable tree structure. Unified user interface as code, computational medium as living book, written in the same universal language.

(Second song “Lisperanto”.)

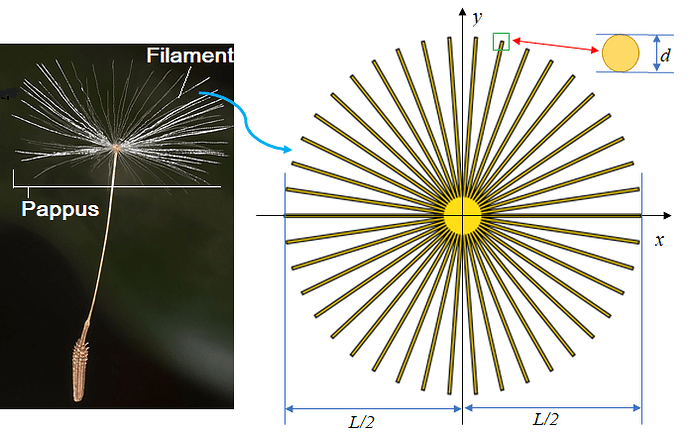

Aristid Lindenmayer, a Hungarian theoretical biologist and botanist, worked with yeast and filamentous fungi and studied the growth patterns of various types of bacteria.

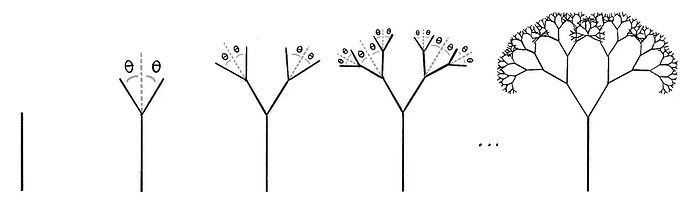

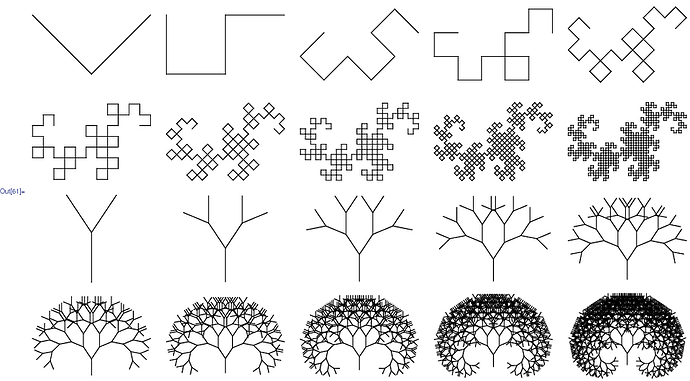

A Lindenmayer system, or L-system, is a parallel rewriting system and a type of formal grammar. It consists of an alphabet of symbols that can be used to make strings, a collection of production rules that expand each symbol into some larger string of symbols, an initial “axiom” string from which to begin construction, and a mechanism for translating the generated strings into geometric structures.

Originally, the L-systems were devised to provide a formal description of the development of simple multicellular organisms, and to illustrate the neighbourhood relationships between plant cells. Later on, this system was extended to describe higher plants and complex branching structures.

How beautiful. I’m making the connection now that this is the same author of The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants (PDF), “the first comprehensive volume on the computer simulation of certain patterns in nature found in plant development.”