This topic reminded me of a book I enjoyed, called Paper Machines.

Why the card catalog—a “paper machine” with rearrangeable elements—can be regarded as a precursor of the computer.

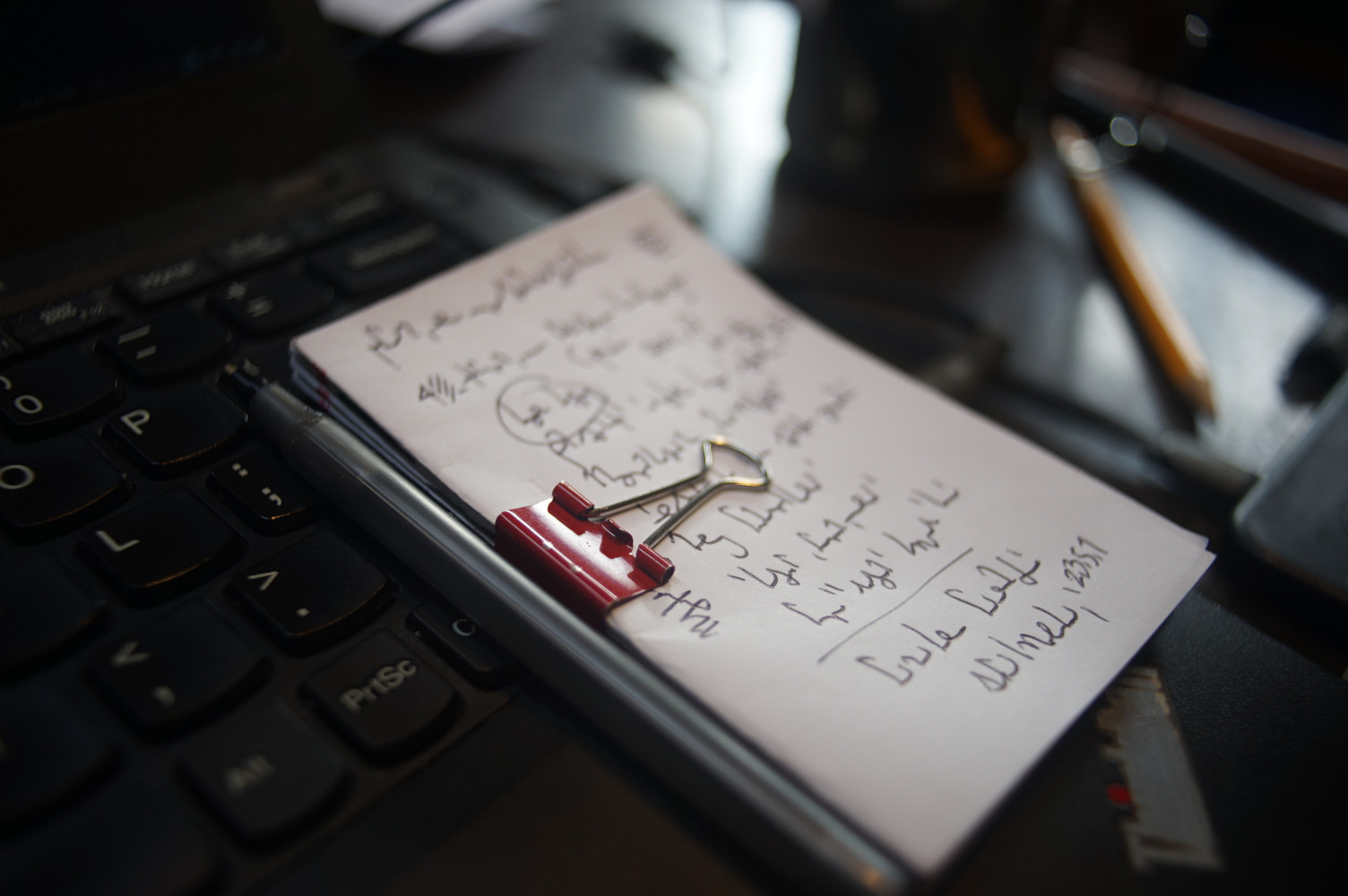

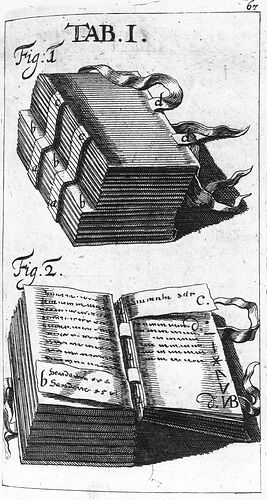

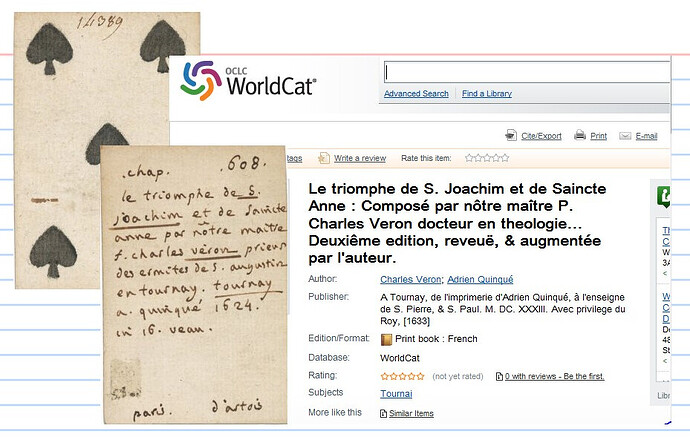

The story begins with Konrad Gessner, a sixteenth-century Swiss polymath who described a new method of processing data: to cut up a sheet of handwritten notes into slips of paper, with one fact or topic per slip, and arrange as desired.

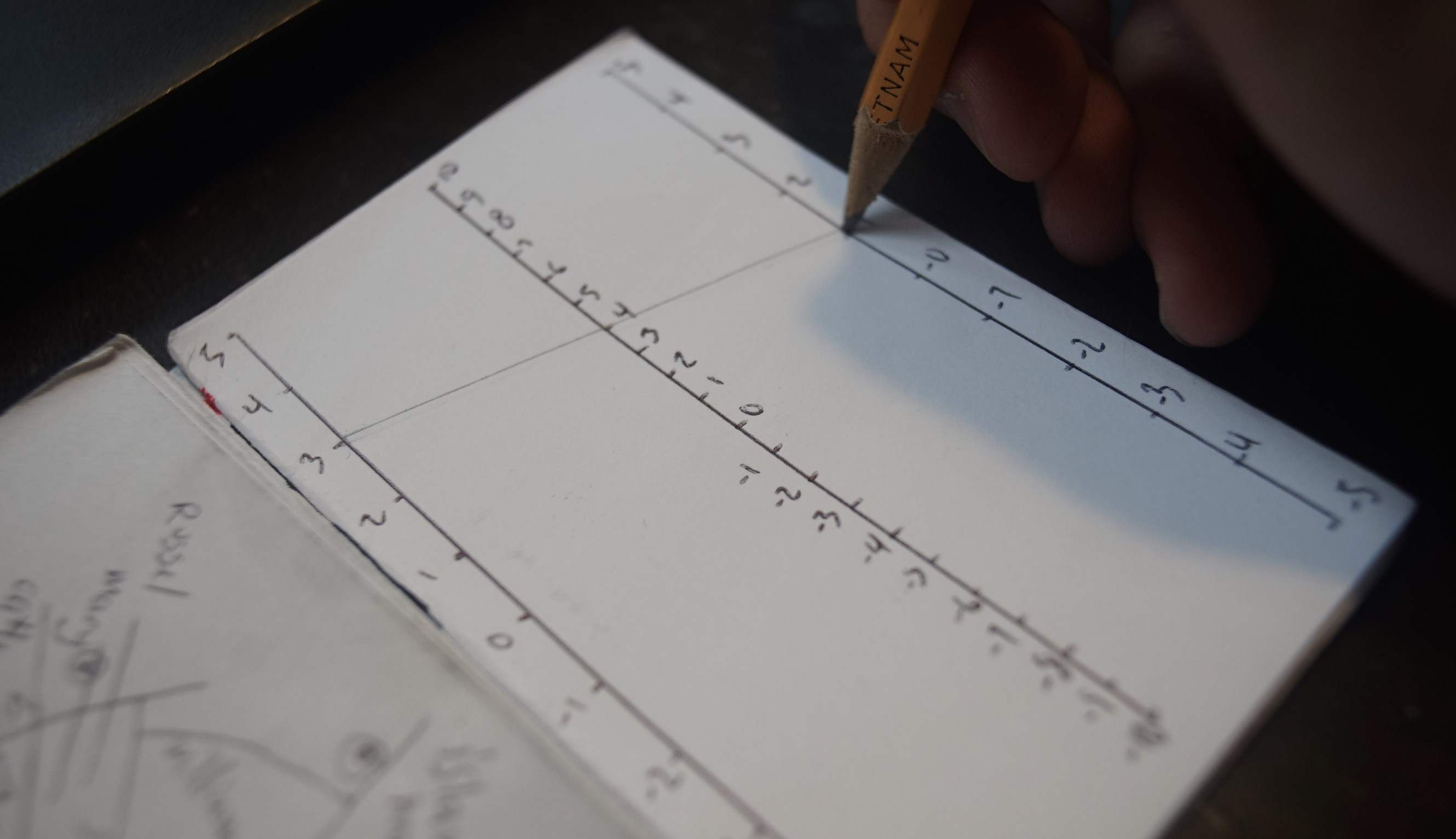

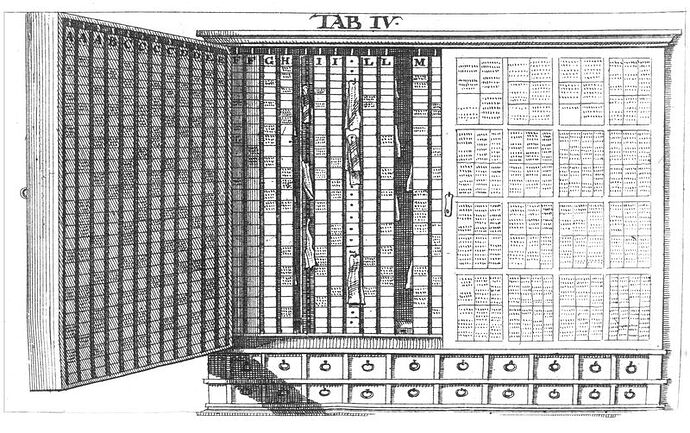

In the late eighteenth century, the card catalog became the librarian’s answer to the threat of information overload. Then, at the turn of the twentieth century, business adopted the technology of the card catalog as a bookkeeping tool.

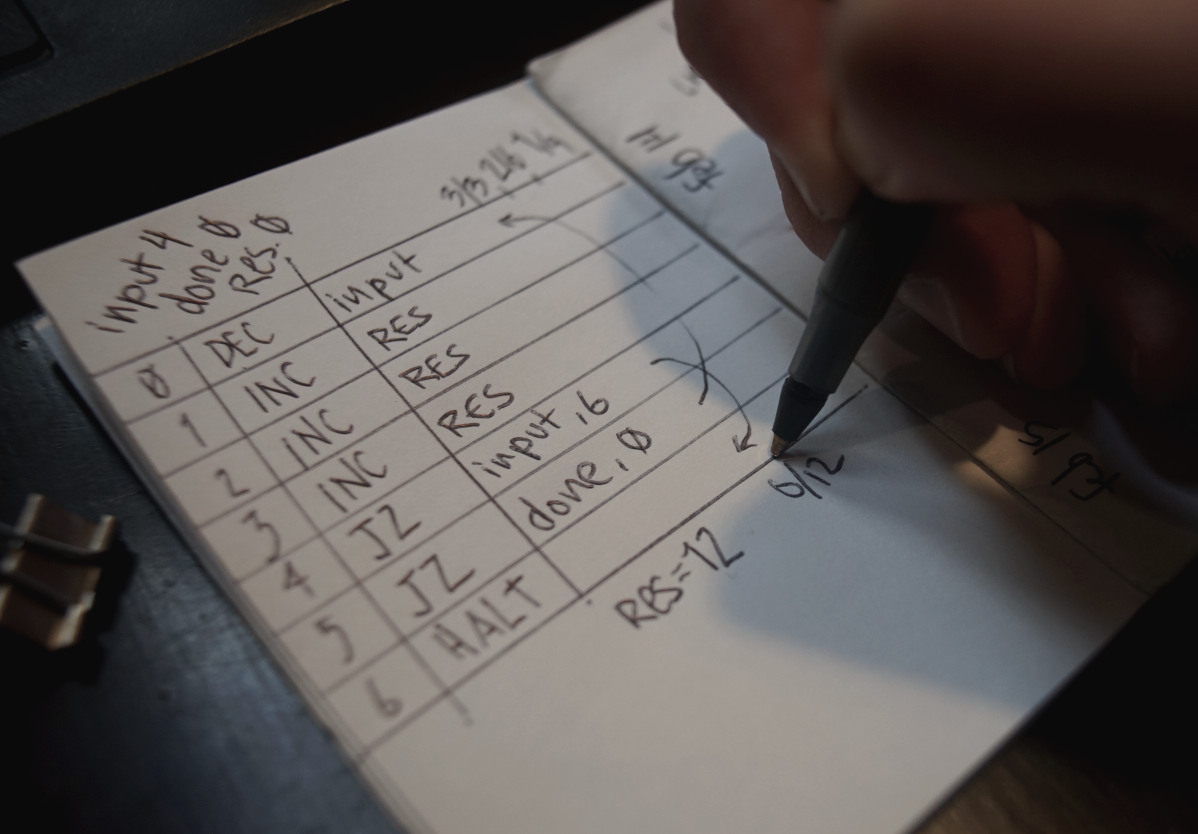

Krajewski explores this conceptual development and casts the card file as a “universal paper machine” that accomplishes the basic operations of Turing’s universal discrete machine: storing, processing, and transferring data.

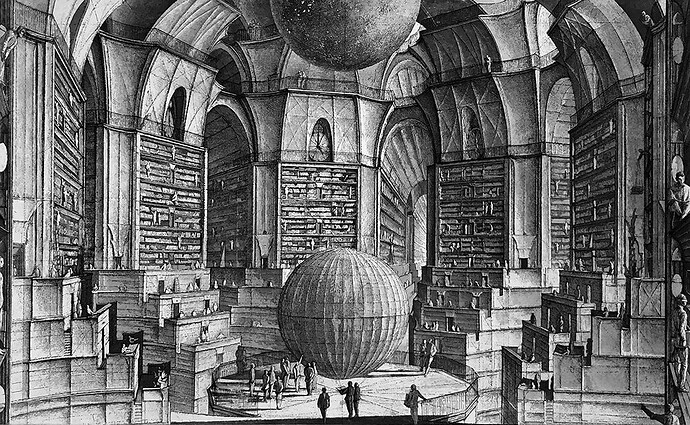

At the outset of his library activity in Wolfenbüttel, Leibniz sketches a detailed plan, aiming to tackle the pitiful mess this famous collection is in. For a library without a catalog, as Leibniz put it in his Consilium, resembles the warehouse of a businessman who cannot keep stock.

If the purpose of a businessman is garnering profits from his products, deploying certain technologies such as double-entry accounting, the comparison concedes that a library full of books remains worthless as long as it does not maintain a single book about these books.

Only a catalog allows specific access to the stored knowledge that can produce profit by way of reading. This insight was later taken up by another famous counselor and writer in Weimar, namely, Goethe.

On the Gradual Manufacturing of Thoughts in Storage

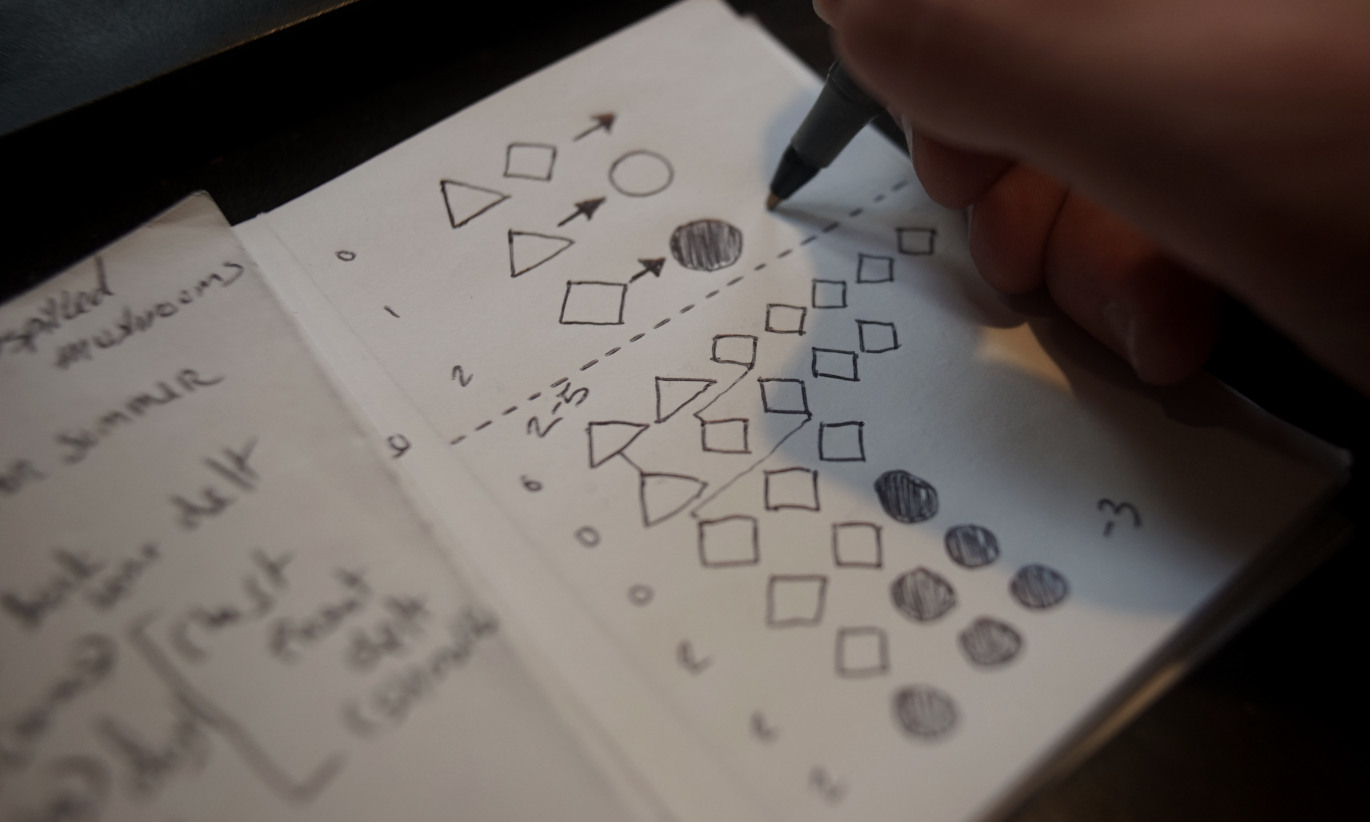

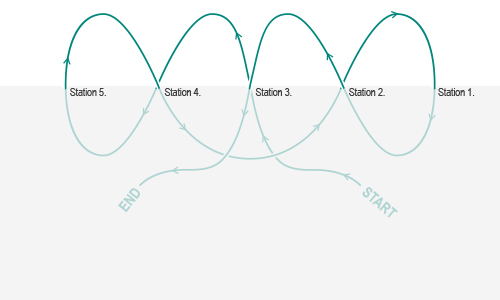

As soon a box of index cards reaches a critical mass of entries and cross-references, it offers the basis for a special form of communication, a proper poetological procedure of knowledge production that leads users to unexpected results.

The premise of this claim (and the basic principle of working with index cards since their “invention” by Konrad Gessner) consists in the fact that innovation never happens ex nihilo (be it a thought, or a text with delicate lines of argumentation, or the creation of an artifact), but on the contrary always includes a recombination of disparate or similar elements. In short, the production of innovations is always based on the fortified recombination of the existing.

The year 1900 sees the founding of System: The Magazine of Business in Chicago, and by 1910 the journal has dismissed contemporary office solutions in favor of the loose-leaf binder, advocating “card index systems” and praising these devices as an immense achievement compared with conventional filing systems.

“Card indexes are books broken up into their components."

The correct choice for one’s company among the variety of systems offered can be made only on the basis of a distinction between writing and reading. The first type, a reading index, is good for accumulating information, stored every now and then as read-only memory. Just as the book used to be considered a depository of knowledge, so the card index replaces the book by means of a more adaptable and “mobile memory.”

An intermediate position is occupied by the second type, the writing card index, because information is stored briefly and disappears just as quickly. Its storage features remain arbitrary and allow for a random-access memory—however, it is precisely addressed.

Already in 1914, Wilhelm Ostwald recognizes that “in the office and in the factory, the transition from the book to the card index has already taken place.."

A book cannot ever provide loose and insertion-friendly arrangements in alphabetical order; glue holds together those things that, according to the dictates of time, belong together.

The inadequacy of the book having thus been declared, salvation can be found only in the card index, whose multidimensional representation remedies the shortcomings of the book.

..So the card catalog was a kind of meta-book of books with indexes and rearrangeable elements.

The book ends its history at the start of the 20th century, and it’s only a few short steps from there to Vannevar Bush’s Memex.

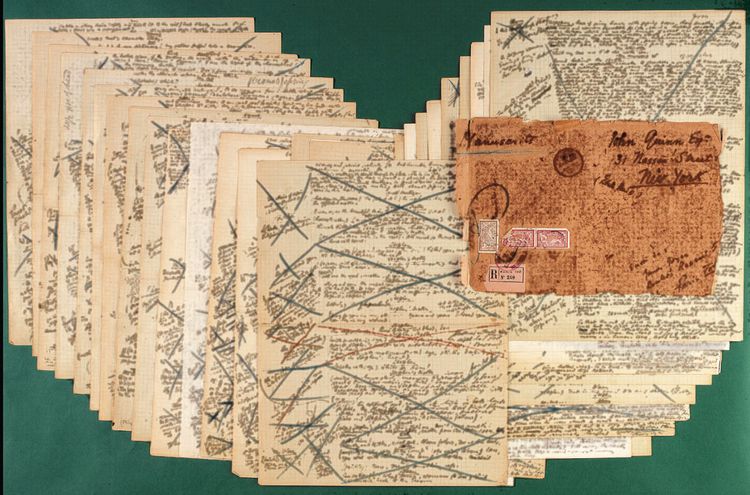

A newly discovered, 27-page manuscript of the ‘Circe’ chapter of James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’ offered at auction at Christie’s Fine Printed Books and Manuscripts sale in New York in 2000.

There are many articles on the “shoebox method”, “notecard system of plotting a book”, “the index card technique”. Apparently there are still some advantages of using paper cards over using a computer.

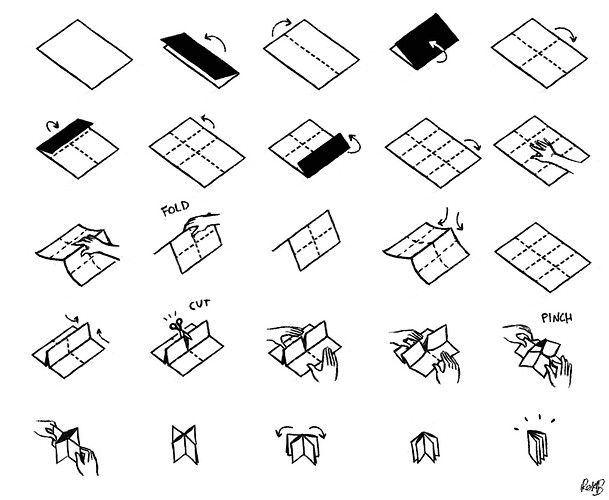

Michael Crichton developed his 3″ x 5″ index-card method of plotting out a story while going to Harvard Medical School.

The cards were easy to take with him every day to class, because they would fit effortlessly in his shirt pocket or in his lab coat. As ideas came to him, he would just jot them down on a card. If a long sequence with dialogue came all at once, he would merely staple those cards together.

At the end of the day, he would throw the cards he had used in a shoebox, and replace them with a fresh batch of blank cards for the next day.

When the shoebox was full and nothing more came, he would take all the cards out of the box, lay them out on a large table, and rearrange his plot by shuffling the cards around into the order he wanted to tell the story.

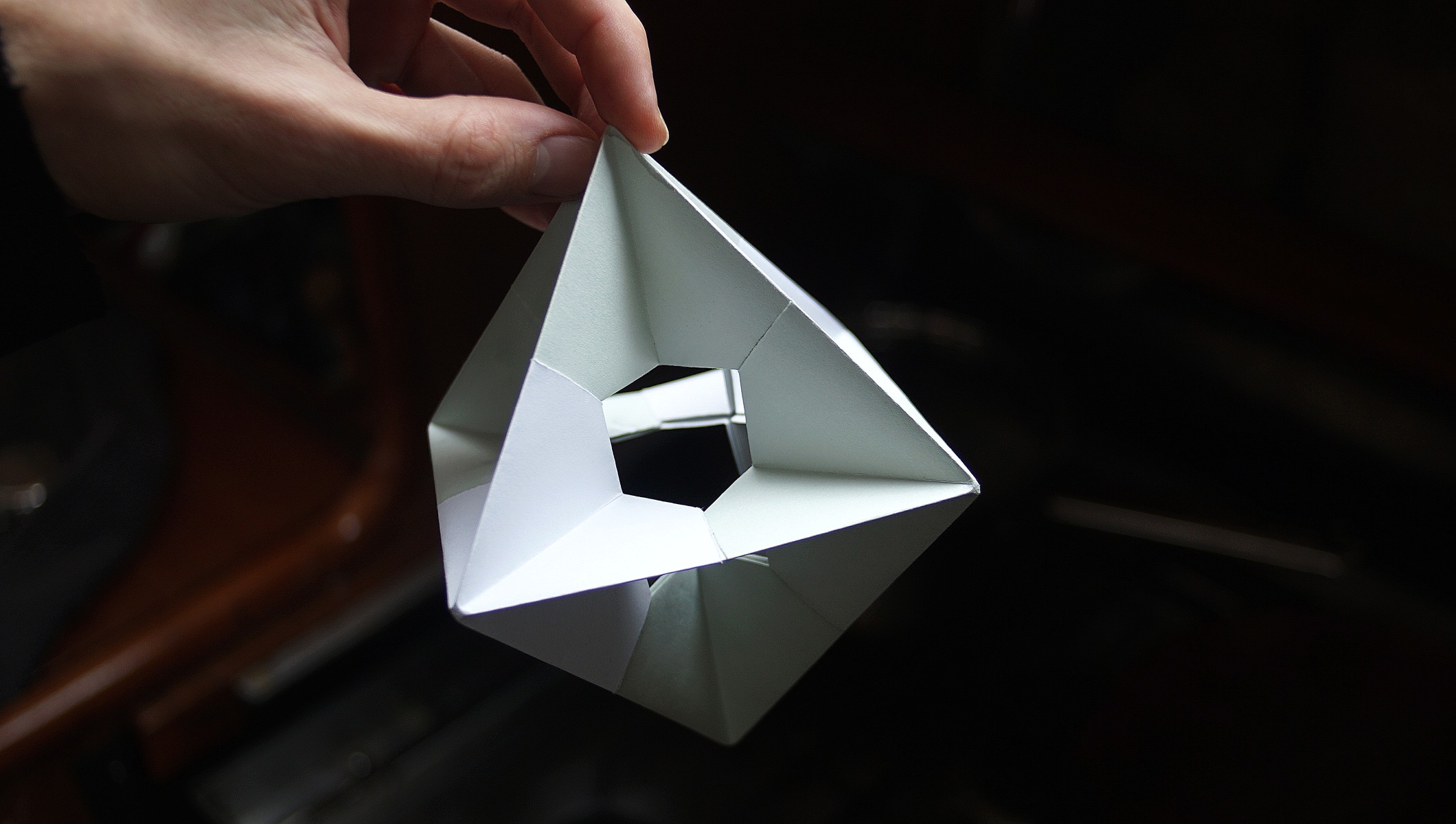

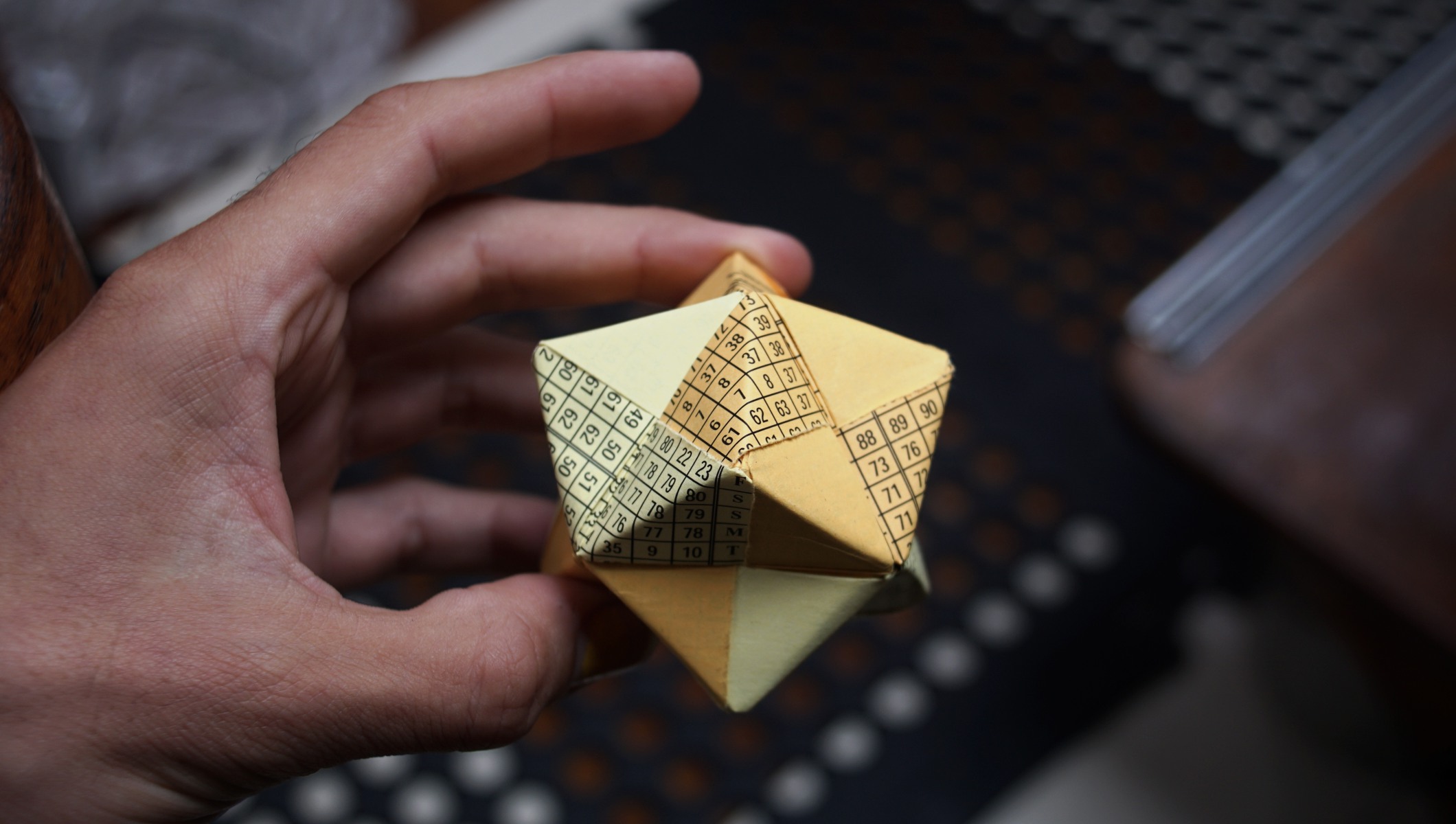

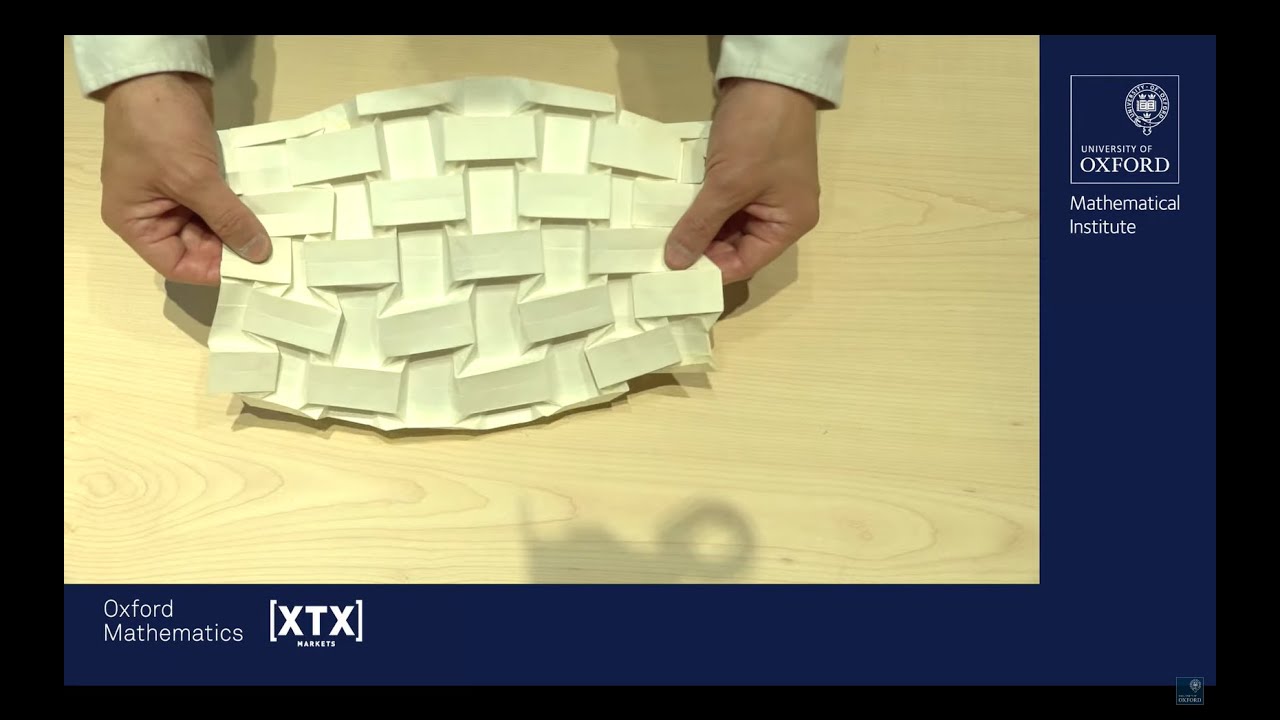

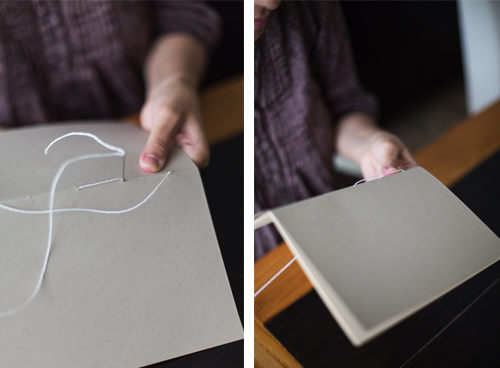

In recent years I hear about “blocks”, like the Block Protocol, which seems like another word for cards with dynamic content. I think one way such blocks can recover some of the advantages of paper is to return to materiality, bring computation out of the box of computers into the real world of tangible objects.

![]()