I recently rewrote a utility to remove all command-line flags configuration options and replace them with a concatenative language, and I think this qualifies as a change that increases malleability. I’ll tell a bit of a story and then some examples.

I maintain the Go reference implementation of the Encoding for Robust Immutable Storage (ERIS). This is basically a minimalist content-address storage system with a better-than-nothing privacy and deniability mechanism.

Someone else wrote the initial implementation and I forked it to fill out the library with features that I needed for my own use-cases. In order to use the library, I needed a utility that exposed the features of the library, so an ad-hoc eris-go utility was created. As more standards that layer on ERIS were drafted I would add those features to the library, and then add a Go-style sub-command to eris-go utility.

Everyone that used eris-go complained about the tedious command-line options. I was fed up with using the flags so I added a JSON config format because I use Nix configuration modules and we like to write our configs in Nix and then reduce them to JSON.

The config file was only a minor improvement. The command-line flags shared a common model with the configuration files so any weaknesses in the model was endemic to both.

I was tasked with adding support for serving static websites as virtual-host mappings to ERIS-FS snapshots. Fitting this into the JSON config file seemed stupid so I gave up on it completely.

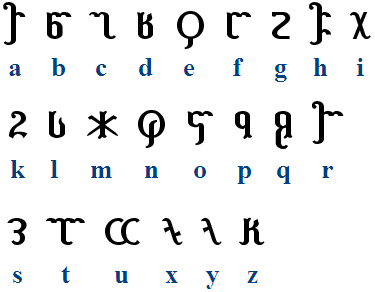

I replaced the sub-command-style eris-go tool entirely with an erishell utility that uses a concatenative language that could be specified entirely on the command-line. The documentation of the language is here.

This is going to be hard to read and is very specific to the application, but try to follow the concatentative mechanism.

A command to decode a stream by fetching blocks using the CoAP protocol and then piping into mpv would be written like this:

$ eris-go get \

-store coap://example.org urn:eris:B4A36J5...

| mpv -

It is now written like this:

erishell \

null- coap- example.org coap-peer- \

urn:eris:B4A36J5... decode- \

1 fd- swap- copy \

| mpv -

I flipped the command-line flags to take arguments from the left instead of the right. Arguments that not recognized as “programs” are pushed onto a stack. Arguments recognized as programs take the stack as input and output new stack. In the previous example the words urn:eris:B4A36J5... decode- are evaluated to a readable stream, 1 fd- is a stream over stdin, and swap- copy- replaces the previous two items on the stack and then copies the stream from the top of the stack to the stream below it.

Obviously this is a convoluted way to write to stdout, but the justification is in composing a storage hierarchy in arbitrary ways, which I don’t think can be done reasonably with a configuration file.

To specify fetching blocks over CoAP, caching them in a git-style xx/xx/xxxx… file and directory hierarchy, caching that in memory, and serving a static website would be done something like this:

erishell \

null- coap- eris.example.org:5683 coap-peer- \

/tmp/eris get- put- or- dirstore- \

cache- \

8 memory-

cache- \

null- http- \

urn:eris:B4A6A… vhost.example.org/ http-bind-fs- \

0.0.0.0:80 http-listen- \

wait-

Difficult to read but I think configuration file with that level of specificity would be worse to reason about.

In the snippet get- put- or- I am placing predefined symbol sets of [ get ], [ put ], and then or’ing to the union set [ get put ]. This becomes the set of options to enable for the dirstore- storage backend, which is to permit read and write operations. In null- coap- and null- http- I am instantiating stateful protocol objects with the null set [ ] because I want to be able to define options later. Defining options as members of sets seems to be a forwards compatible way of specifying boolean option switches. The 0.0.0.0:80 http-listen- program makes a stateful modification to server object on the stack created with http-.

More examples here.

The “user experience” is unpleasant but I discount experience for outcome.

If I was inspired by anything it would be my transcendental experience of replacing a GUI radio automation system with a Liquidsoap script.

I also recently learned TCL properly, and from that I borrowed the model that everything is a string or a collection of strings.