Ink and switch writing about malleable software!

This essay isn’t an exhaustive survey of all work on malleability. For a longer reading list, we recommend the Malleable Systems Collective catalog.

Y’all got a shoutout by name

Ah yes, just saw this as well! Great to see. Hopefully their essay / call to action will nudge more people into investigating malleable topics. ![]()

They’ve had a malleable software “research area” for a few years now:

I think today’s essay helps with approachability by summarising their current thinking. They ask for more people to get involved, and I wholeheartedly agree. A lot more exploration of malleable topics is still needed.

I had a chance of reading a draft of the article as it was being put together, altogether an excellent essay and laudable goal. I’m getting old enough now to have seen these Tools Not Apps conversations as just something that comes back cyclically every couple of years. Don’t get me wrong, it’s great, and I love these. The competition to centralize all of computing into a single ecosystem is as old as .. computing.

An operating system is a collection of things that don’t fit inside a language; there shouldn’t be one.

- Apps are dead, use our Smalltalk app.

- Apps are dead, use our Chrome app.

- Apps are dead, use our ChatGPT app.

- ..

But I’m extremely weary of efforts to formulate a malleable substrate of computation that does not limit itself to making accessible the knowledge to replicate the implementation of the task itself in a lingua franca of the time, in the name of people being disinterested or impatient to learn how things work underneath. This undertone cuts twice as deep seeing that every screenshot in the article comes from an Apple computer, famously hard to customize, and fighting against their own customers’ right to repair and understand their devices. Demoing tools built atop the web, known for eroding the new generation’s grasp of files and local storage, itself a truly decentralized malleable interface.

I worry that demoing web apps built explicitly for cutting edge unaffordable and irreparable proprietary hardware in the name of laypeople inclusivity will lead the reader to the opposite destination than that of an accessible emancipatory technology.

I would elevate the importance of education and documentation as the knowledge of the inner-workings of this substrate is necessarily for the work to be portable and resilient against centralization and control. Ease of use is usually implemented as superficial simplicity, as an additional layer of complexity that hides the underlying layers. Meanwhile, systems that are actually very simple and elegant are often presented in ways that make them look complex to laypeople.

Steve Jobs supposedly claimed that he intended his personal computer to be a bicycle for the mind — But what he really sold us was a train for the mind, which goes only between where rails and stations have been laid down by armies of laborers.

Don’t tell me apps are revolú, and then make me install an app.

One of the very best sentences in the essay, which I wished so hard the essay went on to explore further:

We believe that technical infrastructures for malleable software will need to support sociotechnical systems of people working together, across many levels, to make software work for themselves and their communities.

It’s time to begin dreaming about what those could look like.

This is bit polemical, I wrote it in a single sitting and excuse myself for its harshness.

Against malleable software

When someone tries to zoom in on part of an image and reaches the max-zoom allowed by the operating system, takes a screenshot, and the continues to zoom in more, where is the lack of malleability?

When a kid records their rock climbing on a Sony VX1000, imitating skateboarders from the 90s, transfers the Mini DV tapes to digital via a capture camera connected to their Windows desktop via a firewire port they ordered off Ali Express, which then gets captured by Adobe Premiere Pro so that it can be uploaded to TikTok, where is the lack of malleability?

When I ask Claude a question, copy-and-paste the answer into Google to try and get more information, stumble upon an author, search for the author’s most important book on Libgen, download the IPFS version to my computer, and upload it to Discord to share with friends, where is the lack of malleability?

When someone takes a screenshot of an image from a stock image vendor online, making sure to leave the watermark out of frame, pastes it into Photoshop, exports the collage as a JPEG to their Desktop, opens it up on their phone via a Dropbox sync, and then uploads it to Instagram, where is the lack of malleability?

Software (aggregate) is malleable. Software (singular) has no need to be. You don’t need to read an essay by Kittler to understand that, at its core, the computer is a machine for manipulating ordered sequences of bits.

The malleable part of wood-working, an oh-so-fetishized sibling to software engineering, is the wood. You can plane it, sand it, cut it, screw it, nail it, glue it, crack it, throw it. The tools are ridiculously simple (hammer, circular saw, table saw, sander, etc). The malleability is not in the tool, but between the user and the material.

Software engineers trying to make “malleable substrates for computing” are like woodworkers trying to build the Mega-Jig, one jig that lets you build anything. It’s a fool errand and is blind to how wood-working is done by ordinary users.

Using the computer is messy like a wood-shop floor. It’s impure and hard to replicate. It has side-effects. It’s not like using a closed-off Smalltalk image that can be the same everywhere. These idealized systems are homogeneous. They are Seeing Like The State. They are high modernism. They are attempts by people who like control, who are attracted to computers because they follow their orders, to impose the demand for the same amount of control onto others. It is an inability to cope with otherness, with mess, with excess.

Intead of building a new software substrate, go teach someone how to program. Enzo Mari and Ken Isaacs knew that an instruction manual was invaluable, not for the things you made, but because of the process of making them. The projects in their manuals were merely exercises. As you performed them, you would slowly begin to appreciate the nuances of wood working.

Show a friend what an image really is. Explain how two computers talk to each other. Help them on a task they don’t know how to do. Break down the abstraction, take them down the ladder of abstraction. The goal is for them to be able to wield computational primitives (images, files, sockets, codecs, tensors) like a true hacker.

Again, the malleability is in the user, not the tool.

why would you waste your time telling us you enjoyed it when this is actually a useful critique?

I certainly agree with this statement.

What I worry about is that:

a) we now have several million different computational “primitives”, not just a few

b) because of a, the actual “primitives” that even professional programmers use all involve some form of “first, use a platform managed by one of the Silicon Valley megacorporates”

ie, even the “hackers” aren’t hacking anymore. They’re just plugging in and bowing to the zaibatsu.

I hope I’m wrong.

I did enjoy it, I don’t consider that a waste of time at all, esp not telling Geoffrey of course. The article is solid, and you all should be proud of it. But reiterating the same talking points I always have, stuff I said on the stream, and hold online, stuff we talk about when we grab coffee. I don’t think it’s all that compatible at least not entirely with how the lab operates and where it’s going, and I realize that. Tearing Geoffrey a new one over how the medium is the message, and so on, honestly, not that constructive or even relevant.

But I think my critique is relevant outside of the work the lab is doing when considering malleability as a holistic practice, that’s why this is here. Also, maybe I’m just giving excuses and really, it took me a bunch of days to sit with the paper, read it a couple of times, and question how I feel about it, and by that time it was out.

I’d agree that there are millions of tools, but I still think there are only a handful of primitives that we actually use.

The issue is lack of interoperability between siloes which actually use the same primitives. Solving this is more question of political economy than of technics, and is essential to supporting agency in computing. I think this is one of the most admirable causes to fight for, and one that you become more aware of the more technically proficient you are. (Which motivates making more people technically proficient, as a path towards radicalization.) Critically, however, this has nothing to do with writing more software, nor with making a new OS, or new primitives.

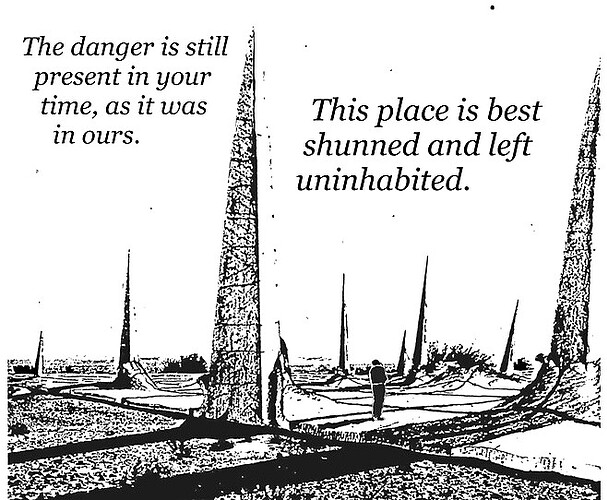

On the other hand, in the land of esolangs and recreational computing, making new primitives is very fun. I love thinking of ways to implement computing on top of a bitmap with replace semantics, or an image-only hypertext system using image-maps, etc… This probably my favorite kind of thought experiment and what motivates most of my explorations in software. Imagine a 10,000 year old video! I just wouldn’t confuse these explorations with helping the political cause mentioned above.

I just wouldn’t confuse these explorations with helping the political cause mentioned above.

The boundaries don’t seem so clear-cut to me. Computing is a young field, and we’re still figuring out how the choice of technical primitives a) affects the technical landscape of how easy something is for a particular group of privileged individuals to learn, and b) interacts with the socio-political-economical landscape of how easy it is for a population to learn in the presence of existing networks of institutions and incentives that we have coevolved with in a very contingent, path-dependent manner. Making new primitives affects b) as well. We as a society create tools, and then the tools change us as a society.

I think there’s a bigger tent here all across the spectrum a) from esolangs, b) to concatenative stacks like Forth or Uxn, c) to things that are still convenient to program and require programming in more mainstream ways like Processing/PICO-8/LÖVE, d) all the way to more custom experiences that the Malleable collective aims for. On one end of the spectrum you require a very specific set of abilities that we have no evidence transfer to the population at large. However, they definitely fulfill certain important criteria of sustainability and performance. They’re not research, they exist right now. On the other end of the spectrum there is the promise of something anyone can use, but it’s unclear if it will fit resource constraints. I’m glad to live in a world where all these options are being explored.

It’s possible the whole world can learn to run the Photoshop->ffmpeg->Dropbox->Instagram pipeline. (And then continually adapt as different parts of that pipeline enshittify in new and interesting ways. All that activity hopefully being adaptive to them on balance.) It’s also possible we need better UIs around the capabilities of ffmpeg before the whole world can put it to use for their situation. What we use affects what people have to learn.

The one that makes me the most mad, that’s purely a political problem, is how incredibly difficult it is to get a playlist off of Spotify.

Sorry, I think that came across as sarcastic, when I mean it sincerely: that this kind of critique is valuable and always appreciated.

I for one understood the spirit in which it was said, I think.

esp Section 3

IMHO one point of malleability is not just that a person can do stuff, but do so fluidly (avoid a lot of menial steps, ie managing the shopfloor), so it adds to and does not take away from their ability to keep the original thought in mind and evolve it very quickly. The sequence that @tobyshooters describe makes me cringe (especially when you extrapolate that to a knowledge intensive like research work, as opposed to leisure tasks, where attention is sparse and critical), because it is possible to visualize a better way to achieve those outcomes had we the wisdom to make software malleable.

It is Moore’s law that has driven the changes, and software which moves at the speed of thought will take time to catch up. So there are as many technical challenges as there are socio-political-economic challenges (all lot of which in part come from compute/networking advances itself).

I’m enjoying reading the discussion here. I want to push back against some of the arguments that’s been made in the thread so far.

@neauoire, thanks for you thoughtful perspective. I can see the argument against using tightly locked down Apple machines for this type of work that embodies many of the values the ‘malleable software movement’ is working against. I’m guilty of this as well — typing on one of those machines right now.

On the other hand, there is also a rhetoric power in showing how software malleability can be achieved in these confines. If it’s possible here, maybe it isn’t as far-fetched or utopian as it otherwise may sound.

But your point have made me think about to what degree my own use of Apple machines (and the like) undermines the potential potency of the work. Then again, I am also an atheist who still pays church tax to the Church of Denmark, so perhaps habits of living with contradictions die hard.

I don’t buy your argument against the Web. I agree that the modern commercial use of the web is undermining digital literacy. I see it with my own kids and their Chromebooks in school. But the Web has great potential for malleability, and Ink & Switch’s (among others’) work on local-first software points to a way this can be combined with a grasp of files and local storage that you’re lamenting is disappearing.

@tobyshooters, I get your point, but I am not convinced by your argument. The development of computational literacy (like any literacy) happens in a dialectical relationship between us and the medium. A medium that restricts our expressive freedom will dampen the potential for development.

As you show, people will creatively overcome friction in ingenious ways, but this is malleability despite the software not because of it.

I simply don’t agree with your point about malleability being in the user, not in the tool. A problem that hinders malleability in computing is that it is very rare that the tool can be(come) the material, that can easily happen in the physical world (even if, yes, most of the time a hammer is just a hammer).

I also don’t know who these software engineers are who are supposedly trying to create mega-jigs. Most of the people I’ve interacted with the ‘malleable software’ community embrace heterogeneity, and that’s been central to my own work as well. Sure, sometimes it is downplayed to demonstrate another point or explore an orthogonal ide, but the “mega-jig” argument feels like a straw man to me.

Finally, I want to push back on: “I just wouldn’t confuse these explorations with helping the political cause mentioned above.”

Sure, if you are just fiddling on your own, the contribution to political change is probably negligible.

But what Geoffrey and co are doing here is not just that. They’re contributing to real technical progress in the direction of more malleable systems, and using their now-established platform to disseminate these ideas in a form that’s appealing to a broad audience both in academia and industry.

(avoid a lot of menial steps, ie managing the shopfloor)

There are great pleasures to sweeping. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kt-VlZpz-8E) Maintenance is an essential part of life, it is what preserves. I would be very careful to disparage or disown it. (https://queensmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Ukeles-Manifesto-for-Maintenance-Art-1969.pdf)

makes me cringe (especially when you extrapolate that to a knowledge intensive like research work, as opposed to leisure tasks

I’d challenge Licklider’s lament that 85% of research is spent doing “clerical or mechanical” activities. My own observations are that, were you not to do that clerical work, you wouldn’t actually produce interesting work. This comes in many forms across many disciplines, but I’ll just note two: (1) Street photographers who spend many days walking 15km, up and down the streets of a city, in order to capture a single shot. (2) Data scientists who spend time becoming intimately acquainted with their datasets, espoused in particular by Andrej Karpathy in A Recipe for Training Neural Networks (1, Become one with the data).

A medium that restricts our expressive freedom will dampen the potential for development.

As you show, people will creatively overcome friction in ingenious ways, but this is malleability despite the software not because of it.

The medium is the computer, and the computer is a superset of tools that can be combined and permuted in infinite ways. (The medium is not one particular tool, no matter how shitty it may be.) What I tried to show is that when one focuses on the boundary objects that are between the tools, you begin to get more of the feel for what a computer is —an already super malleable substrate with so much interesting things to imagine.

What’s restricting our expressive freedom is more tied to trends/education/necessity to learn skills for employment/network effects than the media itself. In particular, with regards to this last item, I agree that the Ink & Switch community can have a sizeable impact in shifting the overton window so that the already malleable nature of the computer can shine through the barnacles of SaaS that have accreted on its surface.

‘malleable software’ community embrace heterogeneity

One thing I’m trying to point out, is that if you look at kids doing Roblox mods or making youtube videos for their friends, if you look at artists trying to produce a work of art, they are comfortable with much much more heterogeneity than our community. The reason that is, is that they don’t perceive it as a flaw, as a mistake in their process. I think Larry Wall’s Perl essay is essential reading on this front (Perl, the first postmodern computer language).

A filmmaker will go on month-long side-quests to produce a whole cinematic world that ultimately gets baked down into a couple of frames of an MP4. They’re not worried that they won’t be able to re-construct the shot in the future. They’re unprecious in what they’ll use to produce an effect. AND THIS IS NOT BAD!

Another way to put this is that, in the computing world, there’s a lot of people trying to make “tools for music production” or “tools for image making” that don’t seem to care much about dancing to music or looking at images. This is a strawman, there are many exceptions in particular in shape of artist who make their own tools, but I think this still points to a fundamental tension when one is too fixated on tools/process instead of artifacts.

Here, I’ll note that I’m personally interested in the relationship between technology and the “avant-garde” of media. You can definitely still make the case, and Ink & Switch does, for improving the quality of life of the average worker who’s relegated to some horrendous workflow inside SaaS hell.

But that does not mean that we go back to the stone age methods. We have built sanitation and electricity and cleaning equipment and what else to make maintenance of said shopfloor faster and less burdensome. I would rather use a vacuum cleaner over a leaf for cleaning. Much as I will use Excel or R to visualize data rather than draw a graph by hand. To become efficient is not disparagement, but common sense.

My experience doing research in 3 different fields has been pretty similar to Licklider. For every example you will produce, I have a counter-example on hand. And even in primitive forms, tools lift our burden and as @akkartik says, computer software is in its infancy.

Not. At. All. Computer Software are human constructs! You cannot blame people that a person (their skill training etc) finds a construct is not conducive to the way they think and act. It is also a rather regressive approach that shifts the blame on end users. It is much more likely that our inability to imagine what software can be is at fault here. I would equally ask how much more creative and productive those artists, kids, and scientists you cite would be if they had software that was more malleable.

Ultimately, your statement is a denial of both Engelbart’s Neo-Whorfian Hypothesis and McLuhan’s famous refrain “Medium is the Message”. Both ideas are foundational to malleable software. The onus is on you to back that up with extraordinary evidence. +1 to @clemens point on dialectic relationship between us and media.

But except for avant-garde art projects, they have moved from film to digital media, because it is so much more useful and powerful. Hear it from David Lynch https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w6Dyl1V_Hvg

Our software and everything about it, much like film, is a dinosaur!

Also, when you talk about filmmakers, not everyone is doing art and have the time and space to explore like that. Most people in the world struggle to make bread and need tools that are intuitively useable.

That is definitely an interesting area to explore. But malleable software is equally intriguing. One does not have to come at the exclusion of another (unfortunately, your comments seem to suggest otherwise).

I agree that the relationship between tools and man is always dialectical, it’s hard not to once you’re confronted with anyone using anything you make.

| Thesis | Anti-thesis |

|---|---|

| Compression, minimality | Exuberance, overflow, excess |

| Agility, self-reliance | Stability, infrastructure |

| Internal coherence | Interoperability |

| Simplicity/Composition | Ease/Banality |

| Transparency | Bootstrapping |

| Direction, where are you going? | Distance, how fast can you go? |

For each of these tensions, you can argue for one of the sides, but the answer will always be some kind of synthetic third. What is lighter, a water bottle you carry on you at all times OR developing city-wide public water infrastructure? The answer is both, neither, in-between.

My goal here is a “torque argument”, which can be straw-manned by calling it a strawman, or understood as a rhetorical/discursive strategy. The point is just to gesture towards the other side of the dialectic, not because it’s correct, but to remind of its existence.

Now, because it is dialectic, I think it’s worth torque’ing in the other direction!

There’s a subtle distinction between explicitly developing tools to make X less burdensome versus to making tools to enable Y, which as a side-effect, makes X less burdensome. I have worked on tools for the former and found myself merely reproducing an old medium in a new one. So I’ve tried to move towards the latter.

I’ve also found that thinking of work as a burden to be a mistake. Here I’d just emphasize the distinction that Arendt makes between labor and work, and not dismiss the latter as the former.

I think you might be misunderstanding me. Of course our tools shape us. I’m very cognizant of the history of media theory and have been largely shaped by these readings. I have almost a decade of little blog posts out there that discuss these ideas.

One important question is at what level of abstraction you call it a tool, and at what level is it the media. Is the medium “the internet,” or “devices that execute instructions”, or “Photoshop”? Are Unix-like pipelines a series of connected tools, or a medium itself? Is it a medium that’s a subset of the general set of networked computers? This all gets very murky, I don’t quite know where to cut it off.

What I tried to suggest is that if you look at the way computers work more broadly, you can see that they are actually quite malleable in present day use!

The place to look at, is much how McLuhan recommended, mirroring Ezra Pound from ABC of Reading, is at the artists of our age, the antennae of the race, the one’s most sensitive to the changes in the media ecology and our sensorial balances.

And, before this gets misconstrued, just because someone calls themselves an “artist” or a “creative” doesn’t mean you should be looking at them for inspiration. It’s not the influencers or the Hollywood directors or the painters featured on Art Forum, or whatever Ai Weiwei is doing.

The people still shooting film are definitely not the avant-garde! It’s pure nostalgia and fetish of large-budgets pushed by Hollywood, enforced by propagating the myth that digital media “looks bad”. And David Lynch was certainly correct in moving towards digital media, something that was picked up much earlier by pioneering pirate TV stations and subcultures like skateboarders.

The people struggling to make bread is not because of a lack of tools! Distribution of wealth is, again, a question of political economy and not technology. We have all the technology we need to increase living standards for all.

I think @tobyshooters, you are misunderstanding and even misrepresenting my comments. So this is my last comment to you, only on some specific misrepresentations. I also wish to hear other voices in this discussion.

Computers by definition are metamedia and hence malleable. It is the choice we make with software that are unnecessarily locking people down in various ways that are well documented in literature. I, for one, but I think this community does not accept this status-quo and believes that we can do better. It is certainly not just or mostly an end user deficiency.

Wait, what are you even responding to (that’s a rhetorical question)? The point here was a response to your broad proclamation, “What’s restricting our expressive freedom is more tied to trends/education/necessity to learn skills for employment/network effects than the media itself.” It is elitist in my view to blame people/society for their lack of learning, especially when the media/technology we are creating, whether accidentally or deliberately, is in many instances exclusionary in nature. It is well documented how technology is being used to create new forms of exclusion. The full comment hence was "not everyone is doing art and have the time and space to explore like that. Most people in the world struggle to make bread and need tools that are intuitively useable."